The Art of Kyoto Cuisine Crafted with Kyoto Vegetables

Representative director of Tankumakita store: Mr. Masahiro Kurisu

What is Kyoto cuisine? It is a difficult question to answer. The origin of how the term Kyoto Cuisine, or ‘Kyo-ryori’ came to be used in the first place is not clearly known, but it is said that the term, ‘Kyo-ryori’ began to be used some time after the Meiji period. The definition of Kyoto cuisine will differ depending on the individual. However, Mr. Masahiro Kurisu says that whatever the word is, the spirit does not change. We asked him about the relationship between Kyoto cuisine and Kyoto vegetable (‘Kyo-yasai’).

Kyoto Cuisine is the ‘Cuisine for Omotenashi’

Kyoto cuisine is an ‘Omotenashi (hospitality) cuisine’, a form of cooking that has been made in Kyoto since the Heian period. Because it is an omotenashi cuisine, (dishes made for services, entertainment, and for hospitality, etc,.) it requires a specialist. During the early Heian period, there was a high ranking position, known as the ‘Ookashiwade no tsukasa’. This was a nobleman’s occupation, who along with his chefs prepared the food for the Imperial court.

Originally, Kashiwade was an occupation for those from the aristocratic family, who were skilled in the use of cooking knives.

It is believed that the commoners from a thousand years ago probably did not use cooking knives to cut fish or birds, as they did not possess cooking knives.

It requires a lot of time to learn and advance in the skill of handling a kitchen knife. Today, the art and skill of using traditional cooking knives continue on the form of ‘Shikibocho’ a cutting ceremony using a Japanese cooking knife.

In the Imperial court, under the Ookashiwade, the chefs cooked food for banquets for guests and this is how the origin of Kyoto cuisine came to be. The term, Omotenashi, back then greatly influenced the country’s political direction. If in the event of an unfortunate case, where the taste did not please the guest, it could have had a negative impact on the diplomatic relationship between the two parties.

Therefore, the chefs had to enhance and sharpen their skills in order to be able to then pass on their knowledge onto their disciples. However, these types of chefs disappeared after an event that changed the way of Imperial life.

That was the Meiji Restoration. The Meiji Restoration began incorporating Western culture, such as Western clothing, Western studies and Western cuisine. As a result, there was no longer the need for chefs, who specialized in cooking Japanese cuisines. Therefore, those who learned the artful skill of cooking Omotenashi foods remained, by opening restaurants in Kyoto. This is the origin of how Kyoto cuisine came to be a part of the Japanese food culture.

The Art of Capturing the Flavors of Vegetables

Those who were in charge of the dining service of the Imperial court were highly skilled. That has to do with the locality of Kyoto.

First, Kyoto is far away from the sea. Therefore, the only fresh fish that they could get was freshwater fish caught from the rivers. Of course, there were no refrigerators at this time, so they were limited to salted and dried fish. Fish such as mackerel and flatfish were dried and were coated with salt. Various techniques were developed in order to eat the dried-fish in a more tasty and enjoyable manner.

One other leading role in enhancing the way of cooking, is the combining of vegetables. Fortunately, it was easy to find an abundance of tasty vegetables. But most people just simply washed, cut and ate the vegetables. This is far from the cuisine of Omotenashi.

In cooking, it is important to be able to have the skill to draw out the flavor of the vegetables from within. You need to use stock (usually made from fish and kelp), combine with fermented foods, and either simmer, or dress in miso, or other sauces, to enhance the flavor of the vegetables. Then, you can combine it with salted and dried fish. This skill takes a long time to develop and it is only found in chefs, who have spent many years refining their skills. This is where the roots of Kyoto cuisine is considered to be found.

A Certain Sense of Aesthetics Required by Chefs

You can produce tasty stocks by boiling ‘konbu’ kelp. By adding a daikon radish to the stock, its flavor will further be enhanced by the stock. You can boil the daikon radish for a quick moment, and add flavor by adding miso and salt. It becomes very delicious simply with the stock that the vegetables is cooked in and the a little of salt and miso for adding extra taste.

We were told from our seniors that white radish must be white when cooked. In other words, adding colours when cooking is not recommended. The color of the food will become dirty.

Here, you can see that the attention in aesthetics has been passed on from the Kuge (court noble). You must not change the color of the vegetable in Kyoto cuisine. To bring out the beauty of Kyoto cuisine is to not change the colour of the food; this is the aesthetic of Kyoto cuisine

That is why soy sauce is not used when boiling, or simmering foods. Stocks made from kelp and mushroom are used to capture the flavor of the ingredients. Only a very small amount of light soy sauce is added at the end, along with a smidgen of salt. This creates the perfect taste and goes well with Japanese sake.

Using Kyoto Vegetables Produced from the Grace of the Fertile Land

It is said that variations of Kyoto vegetable have increased after the arrival of Taiko-Hideyoshi in Kyoto. For instance, it is said that radish from Aichi, grew to be a fat and round radish after planting them in the Shogo-in area. This is known as the Shogo-in radish.

In ancient times, Kyoto basin was a lake, so various nutrients have accumulated at the bottom of the lake making the land very fertile. There was a great lake, like Oguraike near Shogo-in, where the land was blessed with water.

It was possible to harvest lots of Water Shields (Brasenia schreberi), up until 1941 (Showa year 16), before the lake of Oguraike became filled up. Because Hideyoshi comes from a farming household, he knew what to grow and where to grow. He knew that planting Mizuna green in Mibu area would grow well, therefore there is a Mizuna green known as Mibuna.

Kyoto was the capital for a span of 1,000 years, so the flow of food supply was plenty and well developed, brought in from different parts of the country. Konbu (kelp) from Hokkaido was transported first to Tsuruga by the Kitamaebune ship, then across land and then through Lake Biwa, before arriving to Kyoto. The fish from Wakasa Bay was transported via the Mackerel Road and was lightly salted for preservation. Delivering the fish took overnight, covering a distance of 100km from Obama to Kyoto. Transportation took place at night when the temperature was lowest, and the fish had arrived in Kyoto by morning.

These ingredients were then used as part of the Omotenashi cuisine and this is how Kyoto cuisine developed over time, shaped by the geography of Kyoto and its relationship to food producing regions.

Preserving and Continuing the Challenges of the Art of Kyoto Cuisine

My shop, Tankumakita store was founded in 1928, by my grandfather, Kurisu Kumasaburo. It is still in the same location as when it had first opened, which started out with a counter of 7 seats. My grandfather is from the mountains of Tamba. His family was a charcoal maker, but as the third son, he left his home early. Initially, he became an apprentice to learn how to maneuver a boat at Hozugawa-kudari, but then later became an apprentice to learn how to deliver food to a Ryokan (Japanese-style lodging) in Arashiyama. Eventually, he became an apprentice of a chef and after gaining the necessary skills, he became an independent chef. The name of the restaurant where he was trained was called, ‘Tan-ei’, a Ryotei (traditional luxurious Japanese restaurant) restaurant. When naming his own restaurant, he took the ‘Tan’ from ‘Tan-ei” and placed it before ‘Kuma’ (from ‘Kumasaburo’), creating the name ‘Tan-Kuma’. The most important thing is the spirit of Omotenashi, where by tradition the use of water from a well, Konbu (kelp) from Rishiri, and Honkare-Katsuobushi (dried Bonito flakes) from Makurazaki are a must; they are never replaced by other types of ingredients when making Dashi (broth).

However, that does not mean new challenges will not be accepted. New techniques will be incorporated, and we treasure our customers by using the best of the ingredients that are available according to the season. Every single moment counts. This is considered to be the pride of chefs among the masters of Kyoto cuisine.

Information

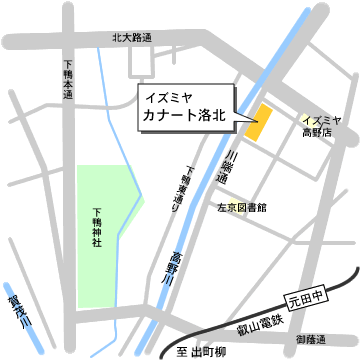

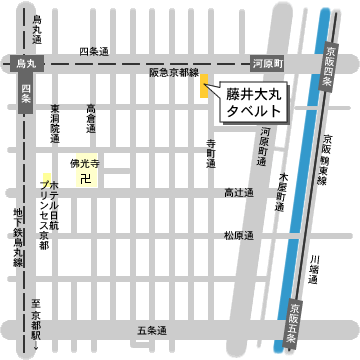

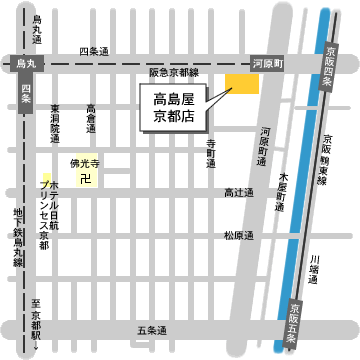

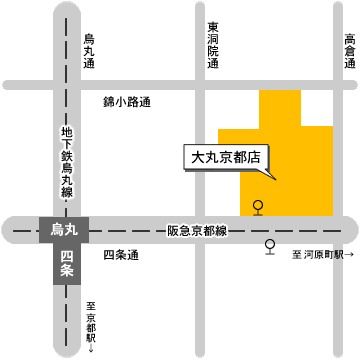

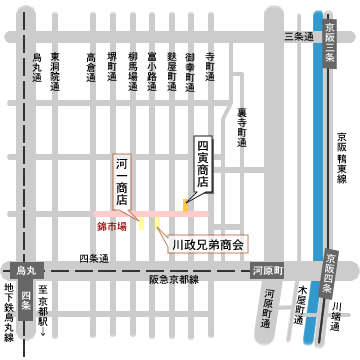

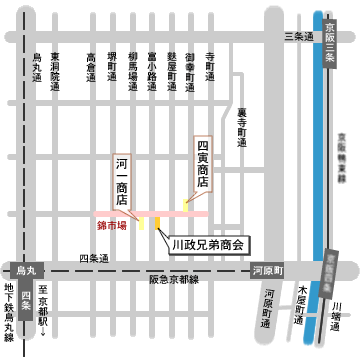

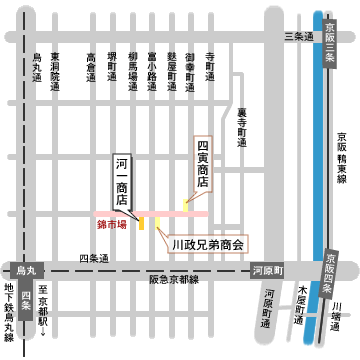

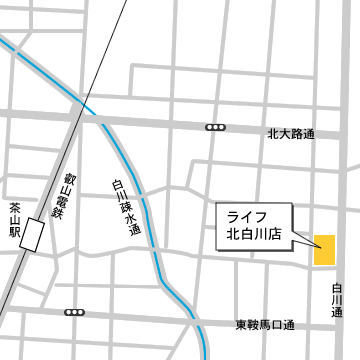

Tankuma-kitamise-honten

- 355 Kamiyacho, Nishikiyacho Shijyo-agaru, Nakagyo-ku, Kyoto-shi

- tel 075-221-6990

- 12:00PM ~ 2:00PM 5:00PM ~ 10:00PM

- Irregular Holidays

- Reservation Required

- No Parking Space

- Lunch 3,500yen ~ 10,000yen Dinner 15,000yen ~ 25,000yen

- http://www.tankumakita.jp/